Analyzing Bitcoin Consensus - Risks in Protocol Upgrades

Introduction

This paper provides an analysis of bitcoin’s consensus mechanism, focusing on the roles of various stakeholders, their powers, and the incentives that guide their actions. Bitcoin is incredibly difficult to change by design. The default is no change. Any significant change needs to pass that hurdle. We categorize the roles people play in bitcoin's consensus into six distinct stakeholder groups, each with their own motivations and influence. We also notice that the relative powers of the stakeholders shift depending on their role in the network’s operation and the stage of the consensus change process. Notably, while Bitcoin Core maintainers do not have excessive power to change Bitcoin, they possess significant power to veto changes. We also introduce the concept of State of Mind, which affects the degree that stakeholders engage in the process of finding consensus.

Historically, changes to Bitcoin's consensus have typically followed a smooth path. However, it is essential to thoroughly explore and understand potential future scenarios that may be more contentious and could lead to a fragile network. This paper presents a novel analysis of the challenges and risks associated with adopting alternative clients. Although alternative clients are an important option, their adoption is difficult to achieve. Soft fork consensus changes can be partially deployed without full consensus, creating a fragile network prone to forks with uncertain outcomes. During a soft fork, investors also have less power than other stakeholders. We highlight the risks of bounty claims in contentious consensus change scenarios involving alternative clients, which increase chain split risks.

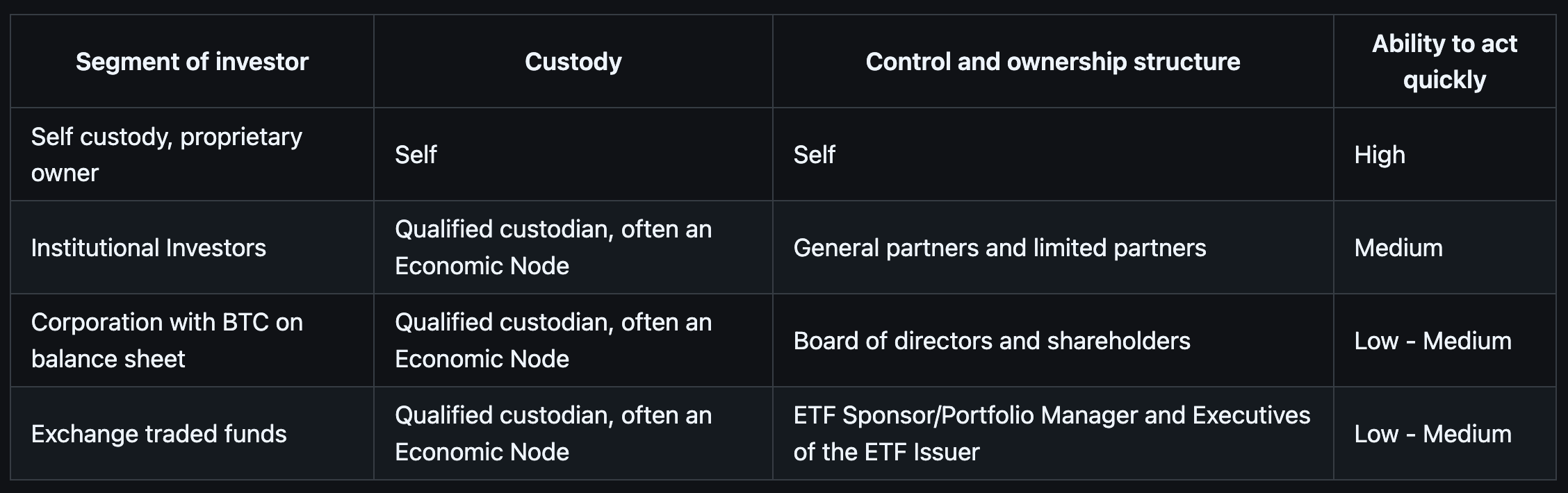

In the event of a hard fork, we observe that not all Investors are equal when it comes to price discovery. Large investor segments may react more slowly, if at all, compared to nimble, self-custodying Investors. Since many Investors do not run nodes themselves, their influence is diminished until a chain split occurs or a futures market develops. Additionally, a stakeholder’s awareness and engagement impact their influence on bitcoin’s consensus; possessing power is ineffective if one is unaware or apathetic.

By examining past consensus upgrades and future scenarios, taking into account the game theory surrounding stakeholder involvement — we aim to enhance understanding of how bitcoin’s consensus is maintained, how it can be changed, and the risks associated with protocol upgrades. Our goal is to equip stakeholders with the tools and frameworks needed to assess and contribute to the evolution of bitcoin’s consensus effectively. We offer recommendations for stakeholders on evaluating proposed changes, including identifying proposals that are maturing toward consensus, asking critical questions about their benefits and potential risks, and determining whether a change has broad support.

What is Bitcoin Consensus

Bitcoin consensus refers to the set of rules that define the validity of transactions and blocks. These rules are encoded in software run by and enforced by the network’s nodes, ensuring that all participants agree on the blockchain’s transaction history.

Technical Aspects of Consensus

Important aspects of bitcoin’s technical consensus include:

- Block Validation: Define what constitutes a valid block, including aspects like block size, block header, transaction structure, and proof of work requirements

- Transaction Validation: How transactions should be structured and what makes them valid, including rules about inputs and outputs, signatures, and script execution

- Chain Selection: Determine which chain is considered the canonical bitcoin blockchain in case of forks, typically based on the valid chain with the most accumulated proof of work

Understanding the technical aspects of consensus is important because any changes to the client software that change these technical aspects of consensus result in either a soft fork or hard fork (described in greater depth below) and the nodes on the network may be required to upgrade and adopt newer versions of the client. For example, new opcodes introduced require a soft fork or hard fork because they affect script execution, making scripts that completed successfully before the fork now terminate in failure (in the case of a soft fork), or vice versa (in the case of a hard fork).

What maintains Bitcoin Consensus

In bitcoin, each major stakeholder group possesses certain powers and is driven by a set of incentives that shape how they are likely to wield those powers. Entities may belong to multiple stakeholder groups, leading them to exercise various powers and navigate a mix of potentially competing incentives. For instance, a wealthy investor might also be a large influencer, or a business could operate an Economic Node, engage in mining, employ Protocol Developers, and have media influence. Additionally, entities can sometimes act against their typical group incentives for ideological or other reasons, meaning incentive descriptions apply to the average group but allow for individual variance. When assessing whether groups should be classified together or separately in terms of their impact on consensus, it is important to consider whether their incentives and powers are meaningfully similar. If both aspects align, they can be treated as the same group for consensus purposes; if they differ, they should be regarded as distinct.

Stakeholders

Economic Nodes

Economic Nodes play a critical role in bitcoin's consensus mechanism. Economic Nodes are full nodes that not only validate and relay transactions but also receive and send substantial amounts of bitcoin payments. These nodes are distinct from nodes just validating blocks and transactions. These Economic Nodes are typically operated by businesses and institutions that handle significant volumes of bitcoin transactions and often serve as bridges between the bitcoin network and the traditional financial system (providing a venue to swap BTC for fiat currencies or other cryptocurrencies).

Economic Nodes, or nodes that regularly receive bitcoin, have power and influence which is proportional to the frequency and volume of payments received. For example, a high volume exchange has power in that if their nodes reject blocks mined by Miners, it would devalue the chain that Miners are building upon.

They include:

- Cryptocurrency exchanges

- Payment processors

- Custody providers

- Large merchants and service providers who accept Bitcoin as payment

- RPC providers (manage and host nodes for application developers)

Powers:

- Ability to define which fork is bitcoin by choosing which version of the software to run and set ticker symbols

- Reject blocks they consider invalid, potentially causing chain splits

- Ability to list or not list markets for spot and derivative markets for forks

- Ability to sell fork coins on behalf of users without their permission

Incentives:

- Maximize transaction volume and trading activity

- Maintain the security and stability of the network

- Comply with regulatory requirements in their jurisdictions

- May have equity investments in bitcoin businesses

Investors

Although Investors do not tend to play a role in the day to day operations of bitcoin, they impact the price of bitcoin by buying or selling. Investors tend to have a thesis for why they hold bitcoin, thus changes in bitcoin consensus that affect their thesis can positively or negatively affect the price of bitcoin and consequently the incentives to Miners for the amount of hashrate security the network has. However, bitcoin's price also has broader implications beyond mining. It can drive venture capital funding for new businesses, affect funding for open-source developers working on software related to bitcoin, and stimulate overall investment, leading to innovation in products and services. Thus, the price of bitcoin not only influences network security but also shapes the development and expansion of the entire ecosystem.

They include:

- Large individual holders of bitcoin

- Active and passive institutional fund holders of bitcoin

- Sovereign wealth funds, central banks, and governments

Powers:

- Influence market prices through buying and selling activity

- Signal preferences for different proposals through futures markets (which could in turn affect choices of Economic Nodes)

- Fund development efforts or advocacy for specific changes

Incentives:

- Maximize the value of their bitcoin holdings

- Maintain or improve bitcoin's properties as a store of value

- Minimize risks of network instability or contentious changes

- Comply with regulatory requirements in their jurisdictions

Investor groups differ in their agility and capacity to influence consensus changes, largely due to variations in their legal frameworks and custodial setups. These differences make it important to distinguish between several key investor categories.

Media Influencers

Media Influencers play a crucial role in shaping public perception, disseminating information, and facilitating discussions within the bitcoin ecosystem. Their influence can significantly impact the direction of consensus decisions by swaying public opinion and amplifying certain narratives that in turn can affect the decision making process of other stakeholder groups.

They include:

- Media and press organizations

- Thought leaders with large followings on social media platforms

- Organizers of conferences related to bitcoin

Powers:

- Shape narratives around bitcoin and proposed changes.

- Distort the perceived support level of a consensus change (either aggrandizing or minimizing) relative to reality.

- Amplify or critique various stakeholder positions.

- Educate the broader public about bitcoin developments.

Incentives:

- Generate engagement and grow their audience.

- Maintain credibility within the bitcoin community. [6]

- Act in their sponsors best interest.

- Often have their own ideological or economic stakes in bitcoin's direction; may fall into one of the other Stakeholder categories.

Miners

Miners are individuals or organizations that use specialized hardware to find a block template and nonce that in combination produce a hash that is less than or equal to the network’s difficulty target. Miners also historically have signaled readiness for consensus upgrades that help other stakeholders determine that it is safer for users to use new upgrades but does not provide a guarantee because the signaling can be spoofed.

They include:

- Individual Miners

- Large scale mining operations

- Mining pools

- Chip manufacturers

Powers:

- Create new blocks, determining which transactions are included.

- Signal readiness for protocol changes through version bits.

- Potentially censor transactions by not including them in blocks.

- Direct hash power to compete for chains in the event of a fork. Each ASIC mining chip can only mine for one side of a fork. [7]

In the current environment, Miners rarely run bitcoin software to construct block templates and thus do not directly control which consensus rules to follow, only a handful of pools do. However, the switching costs are low for a miner to switch to another pool. So if a pool acts against the interests of a miner, they will lose customers. The Miner’s state of mind (SOM) matters, if the miner is unaware or apathetic (SOM3, SOM4) then they might not even be aware it is in their interest to switch pools. In the future, we may see a shift toward Miners running bitcoin software and directly controlling transaction selection and choosing consensus rules with protocols such as Stratum v2 and Braidpool. [8] [9]

Incentives:

- Maximize their revenue from block rewards and transaction fees. [10]

- Maintain the value of their specialized hardware investments.

- Avoid network instability that could threaten the value of bitcoin.

Protocol Developers

Protocol Developers (including the group often referred to as Core Developers) refers to the developers proposing and implementing consensus changes in addition to maintaining the bitcoin protocol and client(s). Protocol Developers do not have unilateral power over bitcoin because the clients that the economically meaningful stakeholders choose to run is what defines the rules of the network. [11] [12] If the Protocol Developers were to make a change to Bitcoin Core that the other stakeholders do not agree with, they would simply not run that version of the software. However, maintaining the reference client is quite powerful because it provides the Protocol Developers with veto-like power because of the difficulties of growing the adoption of an alternative client which we discuss in further detail later in this paper. [13]

Powers:

- Propose and implement code changes.

- Maintain the reference client (Bitcoin Core).

- Provide technical expertise to inform decision-making.

- Have veto(ish) power because of how hard it is to grow adoption of an alternative client.

Incentives:

- Improve bitcoin's technical capabilities and security.

- Maintain their reputation within the developer community.

- Often motivated by ideological commitment to bitcoin's principles.

- May be incentivized by developer sponsorships.

Users and Application Developers

This group represents those who actively use bitcoin for various purposes, from simple transactions to complex financial applications, as well as the developers who create these applications and solutions.

They include:

- Users who use bitcoin as a store of value

- Remittance service providers and users

- Developers and users of payment solutions like Lightning

- Users and developers of Bitcoin-based applications for NFTs (e.g. Ordinals) and fungible tokens (e.g. BRC-20 and Runes)

- Users and developers of Bitcoin-based DeFi applications

- Developers creating smart contract-like functionality on Bitcoin

- Teams working on sidechains or Layer 2 solutions for advanced functionality

- On chain wallet providers

- Equity investors in bitcoin businesses [14]

Powers:

- Often provide the default node connection for users sending and receiving bitcoin transactions

- Sell or threaten to sell one side of a hard fork dispute, but with less scale and impact than Investors.

- Sell or threaten to sell bitcoin and use other cryptocurrencies that meet their needs.

- The amount of fees driven by the application is directly proportional to their power.

Users and Application Developers is a broad group with a spectrum of services and applications. We can break down this group into two segments based on their use case: (1) medium of exchange and (2) utility.

- Medium of Exchange: This segment primarily involves various forms of payments. These applications involve straightforward transactions between two parties and typically do not have multiple users trying to change the same state at the same time.

- Utility: This segment covers more complex transactions financial services such as lending, insurance, NFTs, and trading. These applications often involve multiple users interacting with the same state simultaneously, which can lead to competition over modifying that state (this is often referred to as a write conflict).

The key difference between these two segments lies in the nature of their applications’ transactions:

- Medium of Exchange Applications: Since payments are usually bilateral (between two parties), there is less chance of conflicts arising from multiple users trying to access or modify the same data at once.

- Utility Applications: In contrast, these applications often involve scenarios where many users want to interact with the same asset or state simultaneously. For example, if several users want to trade the same asset in a shared pool, they are all trying to affect the price based on their trades. Because they share the same goal, the sequence in which their transactions are processed becomes important. This can lead to competition over who gets to trade (write to the state) first, which affects the incentives of the developers within this segment.

The above causes a difference in the incentives of these two segments of application developers.

Medium of Exchange Users and Application Developers Incentives:

- Benefits from lower fees: Payments with bitcoin compete with other payment rails on fees.

- Benefits from either larger block sizes or efficient transaction layers that keep fees low or sidestep fees

- Benefits from greater privacy options: Competing payment rails are private, there are merchants and users who might also want privacy for payments on bitcoin.

Utility Users and Application Developers Incentives:

- Less sensitive to fees than Medium of Exchange: Since the activity provides utility beyond just payments (for example, the utility of a loan against BTC collateral could be justified even with high fees whereas payments compete with other payment rails).

- High tolerance for risk: Early developers and adopters of decentralized applications tend to select for those with more risk tolerance.

- Benefits from more programmability: The more programmability is allowed, the more complex the types of applications can be built and potentially the more utility can be provided to users.

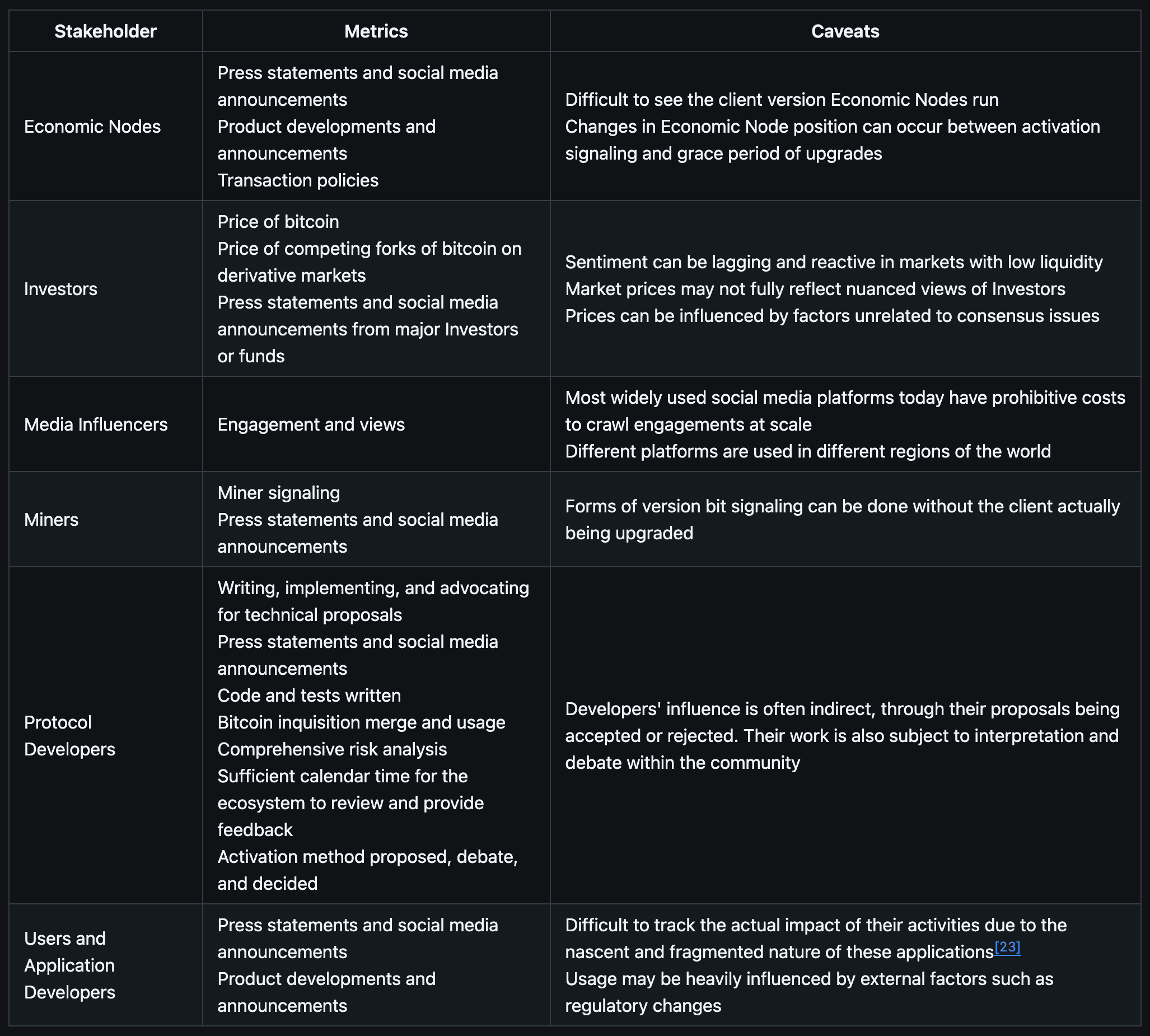

How to measure Consensus

Measuring consensus in bitcoin is a complex task due to the decentralized nature of the network and the diverse set of stakeholders involved. There is no single metric or method that can definitively measure consensus across all groups. Instead, we must observe and analyze various signals and actions from different stakeholder groups. Here is a breakdown of how we might attempt to measure consensus for each group, along with the challenges and limitations of these measurements:

Determining Consensus

Assessing whether a proposed change has achieved consensus can be challenging due to bitcoin's decentralized nature. Consensus is not formalized through votes but is instead gauged by the absence of strong, sustained opposition and the overall sentiment in the community. Stakeholders can look to several indicators and resources:

- Mailing List Discussions:

- Monitor the bitcoin-dev mailing list for technical discussions and debates.

- Newsletters like Bitcoin Optech.

- Look for the level and quality of engagement from respected developers and researchers.

- GitHub Activity:

- Check the Bitcoin Core GitHub repository for pull requests and issues related to the proposal.

- Pay attention to the number and nature of reviews, comments, and revisions.

- BIP Process:

- Follow the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP) process for formal proposals.

- Technical Conferences, Workshops, and Podcasts:

- Watch presentations and panel discussions from events where Protocol Developers and other stakeholders meet

- Look for consensus-building exercises and outcomes from these events.

- Podcasts and YouTube videos

- Miner Signaling:

- For changes that use miner signaling, monitor the percentage of blocks signaling readiness.

- Use block explorers or specialized tools to track signaling progress.

- Node Adoption:

- Track the adoption rate of new node versions that implement the proposed change.

- Use community built tools to monitor node versions across the network.

- Economic Node Statements:

- Look for public statements or announcements from major exchanges, wallet providers, and other Economic Nodes.

- Pay attention to whether they plan to support or oppose the change.

- Community Sentiment:

- While not definitive, gauge sentiment on social media platforms (X, Nostr), forums (e.g. Delving Bitcoin, Bitcoin Talk, Reddit), and at local bitcoin meetups.

- Be aware of potential bias in online discussions and seek diverse perspectives.

- Technical Analysis and Reviews:

- Look for in-depth technical analysis from respected bitcoin developers and researchers.

- Pay attention to security audits and formal verification efforts for critical changes.

- Testnet and Signet Implementation:

- Monitor the implementation and testing of proposed changes on bitcoin's testnet and signet.

- Look for reports of any issues or unexpected behaviors during testing.

- Market Sentiment:

- Derivative markets, including futures contracts on proposed changes or forks, can provide insight into investor sentiment.

- Prices for these contracts can show whether there is a preference for or against a specific proposal.

- User Activation:

- In some cases, user-driven mechanisms, like the User-Activated Soft Fork (UASF), can signal a grassroots movement in support of a proposal, but UASF clients historically have failed to gain adoption from Economic Nodes and their impact has been minimal.

Remember that consensus in bitcoin is not achieved through a single metric or vote, but through a complex interplay of stakeholder actions and reactions. It is important to consider multiple sources of information and to be aware of potential biases or conflicts of interest in any single source.

Stakeholders should remain engaged, stay informed about ongoing discussions, and be prepared to participate in the consensus-building process when appropriate. By carefully evaluating proposed changes and understanding the consensus process, stakeholders can help ensure that bitcoin continues to evolve in a way that preserves its core principles and benefits all users.

To a long, healthy, prosperous bitcoin!